Pass the shiraz, please: how Australia's wine industry can adapt to climate change

Many Australians enjoy a glass of homegrown wine, and A$2.78 billion worth is exported each year. But hotter, drier conditions under climate change means there are big changes ahead for our wine producers.

As climate scientists and science communicators, we’ve been working closely with the wine industry to understand the changing conditions for producing quality wine in Australia.

Read more: We dug up Australian weather records back to 1838 and found snow is falling less often

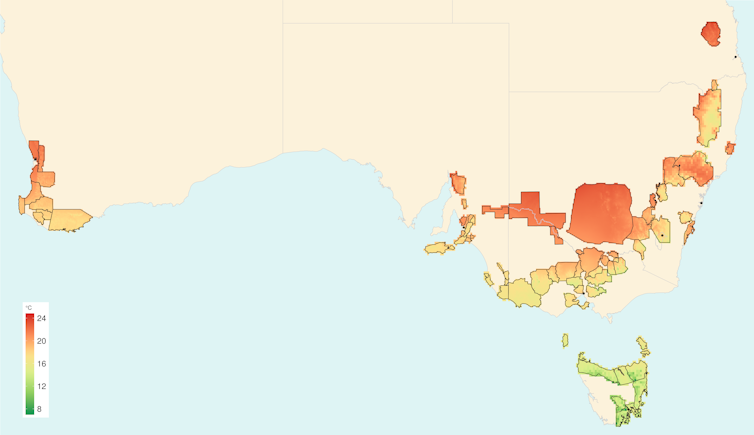

We created a world-first atlas to help secure Australia’s wine future. Released today, Australia’s Wine Future: A Climate Atlas shows that all 71 wine regions in Australia must adapt to hotter conditions.

Cool wine regions such as Tasmania, for example, will become warmer. This means growers in that state now producing pinot noir and chardonnay may have to transition to varieties suited to warmer conditions, such as shiraz.

Hotter, drier conditions

Our research, commissioned by Wine Australia, is the culmination of four years of work. We used CSIRO’s regional climate model to give very localised information on heat and cold extremes, temperature, rainfall and evaporation over the next 80 years.

The research assumed a high carbon emissions scenario to 2100, in line with Earth’s current trajectory.

From 2020, the changes projected by the climate models are more influenced by climate change than natural variability.

Temperatures across all wine regions of Australia will increase by about 3℃ by 2100. Aridity, which takes into account rainfall and evaporation, is also projected to increase in most Australian wine regions. Less frost and more intense heatwaves are expected in many areas.

Read more: An El Niño hit this banana prawn fishery hard. Here’s what we can learn from their experience

By 2100, growing conditions on Tasmania’s east coast, for example, will look like those currently found in the Coonawarra region of South Australia – a hotter and drier region where very different wines are produced.

That means it may get harder to grow cool-climate styles of varieties such as chardonnay and pinot noir.

Some regions will experience more change than others. For example, the Alpine Valleys region on the western slopes of the Victorian Alps, and Pemberton in southwest Western Australia, will both become much drier and hotter, influencing the varietals that are most successfully grown.

Other regions, such as the Hunter Valley in New South Wales, will not dry out as much. But a combination of humidity and higher temperatures will expose vineyard workers in those regions to heat risk on 40-60 days a year – most of summer – by 2100. That figure is currently about 10 days a year, up from 5 days historically.

Grape vines are very adaptable and can be grown in a variety of conditions, such as arid parts of southern Europe. So while adaptations will be needed, our projections indicate all of Australia’s current wine regions will be suitable for producing wine out to 2100.

Lessons for change

Australia’s natural climate variability means wine growers are already adept at responding to change. And there is much scope to adapt to future climate change.

In some areas, this will mean planting vines at higher altitudes, or on south facing slopes, to avoid excessive heat. In future, many wine regions will also shift to growing different grape varieties. Viticultural practices may change, such as training vines so leaves shade grapes from heat. Growers may increase mulching to retain soil moisture, and areas that currently practice dryland farming may need to start irrigating.

The atlas enables climate information and adaptation decisions to be shared across regions. Growers can look to their peers in regions currently experiencing the conditions they will see in future, both in Australia and overseas, to learn how wines are produced there.

Industries need not die on the vine

Agriculture industries such as wine growing are not the only ones that need fine-scale climate information to manage their climate risk. Forestry, water management, electricity generation, insurance, tourism, emergency management authorities and Defence also need such climate modelling, specific to their operations, to better prepare for the future.

The world has already heated 1℃ above the pre-industrial average. Global temperatures will continue to rise for decades, even if goals under the Paris climate agreement are met.

If Earth’s temperature rise is kept below 1.5℃ or even 2℃ this century, many of the changes projected in the atlas could be minimised, or avoided altogether.

Australia’s wine industry contributes A$45 billion to our economy and supports about 163,000 jobs. Decisions taken now on climate resilience will dictate the future of this critical sector.

Gabi Mocatta, Research Fellow in Climate Change Communication, Climate Futures Programme, University of Tasmania; Rebecca Harris, Senior lecturer, Manager, Climate Futures Program, University of Tasmania, and Tomas Remenyi, Climate Research Fellow, Climate Futures Programme, University of Tasmania

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.